You know how it is. All sorts of petty concerns get in one’s way, and somebody’s birthday slips one’s mind. So here’s a belated happy birthday to Russia’s beloved statesman.

You know how it is. All sorts of petty concerns get in one’s way, and somebody’s birthday slips one’s mind. So here’s a belated happy birthday to Russia’s beloved statesman.

Vlad Lenin, the founder of the very same Soviet Union Vlad Putin wants to recreate, thereby reversing “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the twentieth century”, was born on 22 April.

There’s no date of death, for Lenin never died, at least not in the hearts of his grateful countrymen.

That godlike immortality was promised by posters providing the backdrop for my childhood: “Lenin lived, Lenin lives, Lenin will live!” Sure enough, Lenin’s canonised mummy still adorns Red Square, much to the delight of an adoring nation.

A birthday poll conducted by Levada Centre, Russia’s sole credible pollster, proved Lenin’s enduring popularity: 56 per cent of Russians rate him favourably, only 22 per cent negatively and as many neutrally.

As a lifelong champion of arithmetical democracy, I know the majority is always right. Therefore I shan’t say anything against the great man, instead allowing him to speak for himself through his letters:

“It is precisely now and only now, when in the starving regions people are eating human flesh and hundreds if not thousands of corpses are littering the roads that we can (and therefore must) carry out the confiscation of church valuables with the most savage and merciless energy.”

“Superb plan!… Pretending to be ‘greens’ (we’ll pin it on them later), we’ll penetrate 10-20 miles deep and hang kulaks, priests and landlords. Bonus: 100,000 roubles for each one hanged…”

“War to the death of the rich and their hangers-on, the bourgeois intelligentsia… they must be punished for the slightest transgression… In one place we’ll put them in gaol, in another make them clean shithouses, in a third blacklist them after prison… in a fourth, shoot them on the spot… The more diverse, the better, the richer our common experience…”

“…In case of invasion, be prepared to burn all of Baku to the ground and announce this publicly…”

“Conduct merciless mass terror against the kulaks, priests and White Guard; if in doubt, lock them up in concentration camps outside city limits.”

“Comrades… this is our last and decisive battle against the kulaks. We must set an example: hang (definitely hang, for everyone to see) at least 100 known kulaks, fat cats and bloodsuckers; publish their names; take all their grain away; nominate hostages…; make sure that even 100 miles away everyone will see, tremble, know that bloodsucking kulaks are being strangled.”

“Suggest you appoint your own leaders and shoot both the hostages and doubters, without asking anyone’s permission and avoiding idiotic dithering.”

“I don’t think we should spare the city and put this off any longer, for merciless annihilation is vital…”

“As far as foreigners are concerned, no need to rush their expulsion. A concentration camp is better…”

“Every foreign citizen resident in Russia, aged 17 to 55, belonging to the bourgeoisie of the countries hostile to us, must be put into concentration camps…”

“Far from all peasants realise that free trade in grain is a crime against the state. ‘I grew the grain, it’s mine, I have a right to sell it,’ that’s how the peasant thinks, in the old way. But we’re saying this is a crime against the state.”

“I suggest all theatres be put into a coffin.”

“I’m reaching an indisputable conclusion that it’s precisely now that we must give a decisive and merciless battle to the Black Hundreds clergy, suppressing their resistance with such cruelty that they won’t forget it for several decades… The more reactionary clergy and reactionary bourgeoisie we shoot while at it, the better.”

“…Punish Latvia and Estonia militarily (for example follow the Whites in a mile deep and hang 100-1,000 officials and fat cats).”

“Rather than stopping terror (promising this would be deception or self-deception), the courts must justify and legalise it unequivocally, clearly…”

In setting up history’s unique state, the recent birthday boy made full use of his legal training. He knew how to make laws sufficiently open-ended not to limit the state’s self-expression.

For example, Lenin once amended the proposed text of the USSR Criminal Code, one of whose articles stipulated the death penalty for “aiding and abetting the bourgeoisie or counterrevolution.” The great legal mind knew instantly that something was missing, but at first he didn’t know exactly what.

Then it dawned on him: the article wasn’t broad enough. Lenin took his trusted blue pencil out and inserted, after the words ‘aiding and abetting’, an invaluable amendment: “…or capable of aiding and abetting.” And behold, it was very good: anyone could now be deemed so capable and shot.

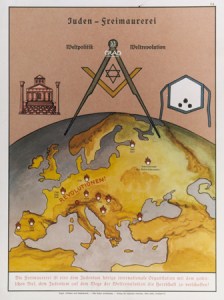

The same broad sweep shines through the excerpts above, something that was beyond the reach of such small-scale copycats as Hitler. Comrade Hitler identified the main enemy with narrow demographic precision: the Jew.

Hence there was a natural genetic and demographic limit on Nazi murders. They knew who was and who wasn’t Jewish, and how many people had drawn that short straw. Comrade Lenin regarded such restraints as amateurish, nay suicidal.

His bogeymen were identified as ‘the bourgeoisie’, but identified doesn’t mean defined. Who were they? Factory owners? Definitely. Landlords? Of course. But what about teachers, engineers, doctors, artisans? Those too, unless they proved otherwise.

Add to them the clergy and the kulaks (peasants, successful or otherwise, who resisted new serfdom), and you realise that the enemy slated for extermination was anyone Lenin didn’t like very much, the kind of people he called “particularly noxious insects”.

That cherished legacy was supposed to have been lost with the demise of the Soviet Union. But Lenin’s namesake is well on his way to restoring it at least partly. As another poster used to say: “Lenin’s cause lives on!”

The world, as we know, is governed by beastly cabals operating in the shadows. They must all be parts of a single network.

The world, as we know, is governed by beastly cabals operating in the shadows. They must all be parts of a single network. Banning the burka is a plank in UKIP’s electoral platform, and that structure is tottering under the impact.

Banning the burka is a plank in UKIP’s electoral platform, and that structure is tottering under the impact. Having said that, Marine and Manny still have ways to go before they catch up with our own Tony Blair.

Having said that, Marine and Manny still have ways to go before they catch up with our own Tony Blair. Having topped the first round of French presidential elections, Manny Macron delivered a rousing oration stressing his patriotic, as opposed to nationalist, credentials.

Having topped the first round of French presidential elections, Manny Macron delivered a rousing oration stressing his patriotic, as opposed to nationalist, credentials. It’s St George’s Day today, and we must all hope that the saint hasn’t yet withdrawn his patronage from England.

It’s St George’s Day today, and we must all hope that the saint hasn’t yet withdrawn his patronage from England. Some 300 years ago, Peter I set out to westernise Russia, “to chop a window into Europe” in Pushkin’s phrase.

Some 300 years ago, Peter I set out to westernise Russia, “to chop a window into Europe” in Pushkin’s phrase. No, this isn’t about those photographs of Mrs Trump naked in bed with another woman. Let bygones be bygones, I say, and anyway she wasn’t Mrs Trump then, much less America’s First Lady.

No, this isn’t about those photographs of Mrs Trump naked in bed with another woman. Let bygones be bygones, I say, and anyway she wasn’t Mrs Trump then, much less America’s First Lady. “I needed to have the confidence and the courage to say this is fine, in fact it’s better than fine,” said Education Secretary Justine Greening.

“I needed to have the confidence and the courage to say this is fine, in fact it’s better than fine,” said Education Secretary Justine Greening. Say what you will about state control over the media, but it offers one undeniable benefit: by watching, say, a state TV channel, outsiders can learn exactly what the sponsoring government is thinking.

Say what you will about state control over the media, but it offers one undeniable benefit: by watching, say, a state TV channel, outsiders can learn exactly what the sponsoring government is thinking.