This morning I caught a glimpse of the Labour slogan and rubbed my eyes to make sure I hadn’t misread. I had.

For a second there I thought it said “F*** THE MANY NOT THE FEW”, which would have been a welcome, if indecorous, display of truth in campaigning.

Alas, a closer examination revealed that the first word was actually FOR. In comes decorum, out goes truth.

Getting back to the truth, on the eponymous date above Britain will go into the most important general election ever. All other elections might have changed the governing party, for a few years. This one may change the country, for ever.

On 11 December Britain will be like any other Western country, better than some (most, as far as I’m concerned), not as good as some others. But within a few weeks of 12 December, she may become hell on earth, in keeping with my little trompe-l’œil.

For, whatever the polls are saying, it’s entirely possible that Corbyn may succeed Johnson, and this is the first time that the words ‘Corbyn’ and ‘succeed’ have been used in the same sentence.

Other parties in other elections wanted to change what Britain does. The Corbyn-McDonnell gang want to change what Britain is.

They don’t want her to remain a moderate country that, despite being mildly socialist, still retains such civilised amenities as basic freedoms, an economy that keeps her close to the top end of world prosperity, justice that’s residually just, a grumbling but generally content populace, a growing but still manageable crime rate.

They want to turn Britain into an Anglophone Venezuela, an impoverished, violent, lawless hellhole in the midst of a civil war, today bubbling just under the surface, tomorrow splashing out in a red mist.

If just half of Labour’s plans come to fruition, and even if sensible people were allowed to choose which half, that’s what Britain will become – overnight and possibly irreversibly.

The economy will collapse almost instantly: close to a trillion pounds has already left our shores in anticipation, with Sir James Dyson leading the exodus. And Dyson is a British patriot, with not only financial but also emotional capital vested in the country.

Foreign capital, unburdened with such ties, will get out immediately, while the getting is good. Our AA credit rating will go in the blink of an eye: financial markets won’t want to do business with a country where business is regarded as evil, where property is insecure and capital is in danger of confiscation.

Wealth producers will stop producing wealth, or rather they’ll produce it elsewhere. Wholesale nationalisation, extortionate taxation, our customary red tape turning into iron chains will put paid to our prosperity, which is unimaginably high in the historical perspective.

Economic catastrophe won’t be short in coming, but that isn’t the whole story, not even the half of it. For economic repression on a scale planned by Labour is bound to lead to political oppression.

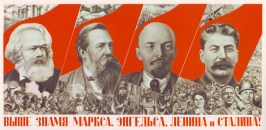

No government has ever succeeded in robbing the people in such a decisive fashion without causing a violent response. Even in Russia, with no tradition of liberty whatsoever, wholesale robbery by the new communist state resulted in a civil war and millions of victims.

Granted, the Bolsheviks resorted to violent repression even before such a reaction, but then the freedom-loving British aren’t Russians. It would take less provocation to set them off.

Nowhere in the world has a political programme akin to one planned by Labour ever been carried out without every liberty being severely curtailed – and without violence perpetrated by the state and those resisting it.

The British haven’t so far had the occasion to develop vigilance against such upheavals, and it’s natural that complacency should set in. People here simply don’t believe that a Venezuela or Zimbabwe can arrive at these shores – but it can.

Civilised institutions take centuries of loving nurture to build, but they can be destroyed in an instant of hateful assault. If history teaches anything, it’s that. Alas, history also teaches that nobody learns from it.

I pray that won’t be the case here, and I hope you’ll join me. But prayer alone isn’t enough (don’t tell Fr Michael I said this).

We must all approach the upcoming election with the gravity it deserves. For a start, this means putting aside resentments, rancour, ideological animus, enmities.

Rather than indulging such red-hot emotions, we must activate ice-cold thinking. Voting guided by febrile emotions – or principles, call them whatever you like – can at this stage be tantamount to national suicide.

All of us – Leavers and Remainers, Tories wet or otherwise, even some Labour members – should ask ourselves a simple question: Would Britain and the British be better off with Corbyn as PM, McDonnel as Chancellor and Abbott as Home Secretary?

If the answer is an emphatic no, as it has to be for anyone other than those bereft of brains but possessed of hate, envy and a desire for revenge, then the next question ought to be the quintessentially British query: What are we going to do about it?

Let’s start by not treating 12 December as a second EU referendum, which is an easy impression to get from our press.

All the Leavers among my friends, which is to say all my friends, are unhappy with the deal Boris Johnson has negotiated. It’s not the kind of Brexit we’d like, but – this can’t be overemphasised – it’s the only one we’re going to get, for the time being.

If tactical voting for the Brexit Party or, nostalgically, UKIP splits the vote and ushers Corbyn into Downing Street, we’re likely to stay in the EU until it disintegrates of its own accord, which I hope will be soon.

Even those whose heart is in their EU home, to paraphrase the revolting flag flown by the Hammersmith & Fulham Council, must decide if they’d want to remain if that meant the national catastrophe of a Trotskyist government, with its ensuing impoverishment, disintegration of social order and tyranny.

Whether we want a better deal, no deal or no Brexit, we must remember what’s at stake on 12 December. Not to be too melodramatic about it, it’s our country, ladies and gentlemen.