‘Culture vulture’ is often misused to mean ‘art lover’, which, in that sense, is dubious ornithologically. However, the term gains validity as it moves closer to its literate meaning.

Vultures are, after all, scavengers that mainly devour the carcasses of dead animals, but at a pinch will prey on the wounded and the sick. Hence, if you agree that our culture is dead or at least ailing, the dictionary definition snugly fits HMG’s culture functionaries.

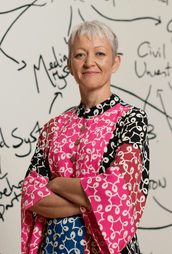

Such as Maria Balshaw, director of the Tate galleries and museums, a culture vulture par excellence. For outlanders among you, Tate is one of Britain’s most venerable and important cultural institutions. That’s why its director is appointed by the prime minister personally.

Since Miss Balshaw ascended to that post during Dave Cameron’s tenure, he must have felt she had the necessary qualifications. That’s par for the course.

In my charitable mood I’d call Dave’s own cultural tastes demotic. In my more normal mood I’d call them barbaric.

For example, he names Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon as his favourite album of all time. That by itself should have disqualified him from 10 Downing Street – if only because the resident at that address may choose the director of Tate.

If the PM is himself a culture vulture, he can be confidently expected to choose another vulture as his appointee. Birds of a feather… and all that.

To vindicate this proverb, Miss Blashaw implicitly restates her commitment to cultural subversion in every word she utters publicly. She has no regard for the great art of the past and much admiration for modern ‘conceptual’ perversions.

And it isn’t just words. In her previous job as director of Manchester City art galleries, she left her mark on every one of them, including Whitworth. That gallery isn’t blessed with too many masterpieces, but one of them is a The Crucifixion, attributed to Duccio.

Since Miss Balshaw has never seen a masterpiece she couldn’t hate, she mothballed The Crucifixion so thoroughly that today’s staff don’t even know what it is or where it is. Thus nothing could distract grateful visitors from what passes for art these days.

Miss Balshaw is strong on ideology, but her grasp of her field is tenuous. This she proved by her selections on Desert Island Discs, a radio programme first heard in 1942.

Again, if you don’t happen to be British, the programme’s guests are asked to select eight records they would take with them to a desert island, where they could conceivably stay for the rest of their lives.

It’s a jocular proposition, but it can yield serious insights into the guest’s personality. For example, a politician whose selections include the Horst-Wessel-Lied and other works in the same vein may raise legitimate doubts about his fitness for office.

Miss Balshaw’s choices for her insular solitude certainly prove she isn’t fit to lead Tate, In fact, she ought to be barred even from visiting it. For she’s prepared to spend the rest of her life listening to nothing but Ghost Town by The Specials and Crown by Stormzy, with these two albums serving as bookends for six other similar ones.

I have no way of reproducing the neurologically murderous sound of this ‘music’, but I can give you a taste of the lyrics Miss Balshaw would be prepared to hear every day of her life.

Thus Ghost Town:

Some day we gon’ set it off

Some day we gon’ get this off

Baby, don’t you bet it all

On a pack of Fentanyl

And here’s Stormzy’s Crown:

You can’t hold me down, I still cope

Rain falling down at the BRITs, I’m still soaked

Tried put a hole in our shit, we’ll build boats

Two birds with one stone, I’ll kill both (What?)

Pray I never lose and pray I never hit the shelf (Two)

Promise if I do that you’ll be checkin’ on my health (Cool)

If it’s for my people I’ll do anything to help

If I do it out of love…

These verses make sense, don’t they? As much as the music Miss Balshaw enjoys and the art she favours, which leaves me in two minds.

I can’t decide whether her appointment constituted a greater insult to culture or to public administration. What do you think?