In May, 1939, a French socialist appeaser wrote an article arguing that Hitler’s claim to Danzig was just.

And even if it wasn’t, Danzig was so far outside France’s national interests that no sane Frenchman would want to die for it.

In fact Mourir pour Danzig? was the article’s title, and it soon became a popular slogan. Left Bank lefties led by Jean-Paul would mouth it sneeringly while sipping their kirs at Les Deux Magots.

Four months later they received a tangible proof that appeasement doesn’t work. On second thoughts, perhaps it would have been better for a couple of thousand soldiers to die for Danzig than for some 40 million to perish over the next six years.

The outbreak of history’s bloodiest war also illustrated the danger of interpreting national interests in a narrowly selfish way. If no man was an island to John Donne, surely no country is “entire of itself”, not in modern times.

Ours is an age of blocs and alliances, not two families jousting with the support of their retainers. When evil giants get bellicose, no single country can resist them on her own.

Or perhaps this general statement can be slightly modified. Conceivably, should China or Russia attack the West, the US could possibly resist either one (not both together) on her own – but shouldn’t have to.

For the US is a member, and the leader, of the Atlantic alliance. And Article 5 of the NATO Charter specifies that an attack on one member is tantamount to an attack on all.

One hopes that NATO’s commitment will never again be put to a test. But if it ever is, let’s remember that NATO, along with its Charter and its every article, has little other than symbolic value without America’s wholehearted commitment.

Only the United States has a nuclear arsenal to match that of Russia (China is a threat too, but a less immediate one). And only the United States can beef up NATO’s conventional capability to a point where it can stop any Russian aggression.

As Russia is about to launch a military exercise involving 300,000 men and 2,000 units of armour, now is a good time to contemplate the danger Putin’s junta presents to her former satellites and Europe in general.

Only an ignoramus, idiot or fanatic would ignore the demonstrable fact that Putin regards the West, the US in particular, as a deadly enemy. Yet no member of those three groups can be persuaded by either reason or facts, so I shan’t even bother.

If I did bother, I’d focus especially on the nuclear blackmail practised at every level of Russian government with monotonous regularity. Putin and his stooges like to brag about Russia’s ability to turn America to radioactive ash, wipe Florida off the map or even to create a North American Strait, meaning clear blue water between Canada and Mexico.

Throughout the Cold War, the West relied on the Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD) doctrine as a means of containing Russia. The terrified public was treated to calculations of how many times over the combined nuclear arsenals of the US and the USSR could destroy the globe.

Only a madman would ever consider using nuclear weapons at the risk of creating a global apocalypse, was the prevalent thinking in the West. That thinking was questionable then, and it’s criminally wrong now.

The Soviet military doctrine proceeded from the assumption that nuclear war was winnable. The current Russian thinking is similar, if more nuanced and perfidious.

Keeping the cosh of nuclear blackmail behind his back, Putin probes the West time after time, putting his toe in the waters of military conflict, going a bit deeper each time.

While one should be careful about comparing Putin to villains of yesteryear, a parallel with Hitler’s strategy in the late 1930s is obvious.

The Nazi führer also refrained from plunging into a full-blown war at once. He’d take a tentative step and watch the Allies’ reaction. Ruhr, Austria, Munich ultimatum, Czechoslovakia, Nazi-Soviet pact – no action on the part of the Allies. Attack on Poland – the Allies declared war, but only of the phoney variety.

Then and only then did Hitler launch a frontal assault on the West, after the Allies had ignored numerous opportunities to nip Nazi aggression in the bud.

That’s how evil dictators work: they pounce only when reasonably certain of impunity. Putin has to play evil dictator, for without a good performance in that role he wouldn’t be able to remain what he is: the chieftain of history’s first global mafia family.

Rather than reinventing the wheel, he adopts, mutatis mutandis, Hitler’s strategy of a step at a time.

Attack on Chechnya precipitated by Putin’s lads blowing up Moscow blocks of flats and blaming it on the Chechens – the West is silent (note the parallel with Hitler’s using the false flag raid on the Gleiwitz radio station as a pretext for the offensive against Poland).

Unprovoked attack on Georgia – hardly even noticed in the West.

Poisoning a British subject with polonium in London – feeble protests only.

Annexation of the Crimea – some token sanctions. Subsequent stealing of a chunk of Ukrainian territory – slightly stiffer sanctions, hitting mostly regular Russians, an insignificant group to the ruling mafia.

Murdering 298 people aboard Malaysian Flight MH17 – a slap on the wrist.

Indiscriminate bombing of Syrian civilians – nothing but thanks from the West.

Attempted murder of more British subjects in Britain, followed by lethal collateral damage – more sanctions.

Hybrid war on the West, including meddling in elections… well, you get the gist.

Putin’s aggression is on an upward escalator that’ll never end. No one knows where the next stop will be, but suppose for the sake of argument that it’ll be an attack on one of the Baltic republics, all NATO members.

This supposition isn’t a stab in the dark. Putin has pledged to restore Stalin’s empire to its past borders, and so far the Botox Boy has been true to his word.

So what about Article 5 then? Will NATO comply with it and defend the victim by force? Will anyone want to die for, say, Tallinn?

I doubt it – and would even if a different man occupied the White House. With Trump in residence, I’m sure today’s heir to Hitler and Stalin will get away with it.

For Putin’s nuclear blackmail is succeeding. Many indirect signs suggest that Western leaders believe that, if the Russian juggernaut is stopped by conventional means, Putin won’t hesitate to go nuclear.

Whether he will or won’t is a moot point. In such matters, perception is reality, and the West’s perception seems to be that Putin just may be mad enough to use nuclear weapons – while we aren’t mad enough to respond in kind.

Iron resolve on the part of NATO, especially the US, is the only possible deterrent, but, during this presidency, America’s resolve to comply with Article 5 is more cotton wool than iron.

A Fox News interviewer asked recently if Trump, whose admiration for Putin is only matched by his contempt for his NATO allies, would be prepared to defend Montenegro (a NATO ally since last year) should it be attacked by Russia.

In response, Trump seemed to discount the possibility that Russia would attack Montenegro (a country that had only barely survived a Putin-inspired coup), while seriously considering the possibility that Montenegro might attack Russia.

At least that’s what his gibberish meant, when he said: “No, by the way, they [Montenegrins] have very strong people – they have very aggressive people. They may get aggressive, and congratulations, you’re in World War III.”

But, Mr President, if those aggressive Montenegrins do launch an assault on Moscow, Article 5 doesn’t say we must jump in. NATO is a defensive compact, and that Article could only be invoked in the marginally likelier event of a Russian attack on Montenegro.

Now Trump has on numerous occasions refused to commit America to Article 5, or indeed to continued membership in NATO. He’d utter words to that effect, then reverse himself after a public outcry. But it’s clear where his heart is.

Of course the example of Montenegro was purely hypothetical. What Russia sees as an immediate target is the post-Soviet space, especially the Baltics.

Trump has a definite view on those countries too. “Estonia,” he once explained, “is in the suburbs of St Petersburg,” meaning that Putin’s claim to her is as valid as Hitler’s was to Danzig.

Considering that Tallinn is 200 miles from Petersburg, the same distance as between Paris and Brussels, the suburbs of Putin’s native city are rather sprawling. But the message wasn’t geographical. It was geopolitical.

Be sure that Putin got it in every tonal detail: while Trump is president, the risk of war over expansionist aggression towards Russia’s neighbours is minimal. Proceed with caution and all that, but do proceed.

However, those strong and aggressive Montenegrins should watch their step: they can’t count on NATO’s help if they drive their tanks 3,500 miles to Russia, violating en route the sovereignty of Romania, Moldova and the Ukraine.

They stand warned – and so are we. I don’t know if the Montenegrins will heed the warning. I doubt we shall.

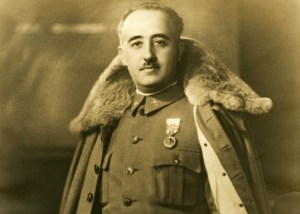

Spain’s socialist government has decreed that Francisco Franco no longer deserves to have his remains interred in the Valley of the Fallen memorial.

Spain’s socialist government has decreed that Francisco Franco no longer deserves to have his remains interred in the Valley of the Fallen memorial.